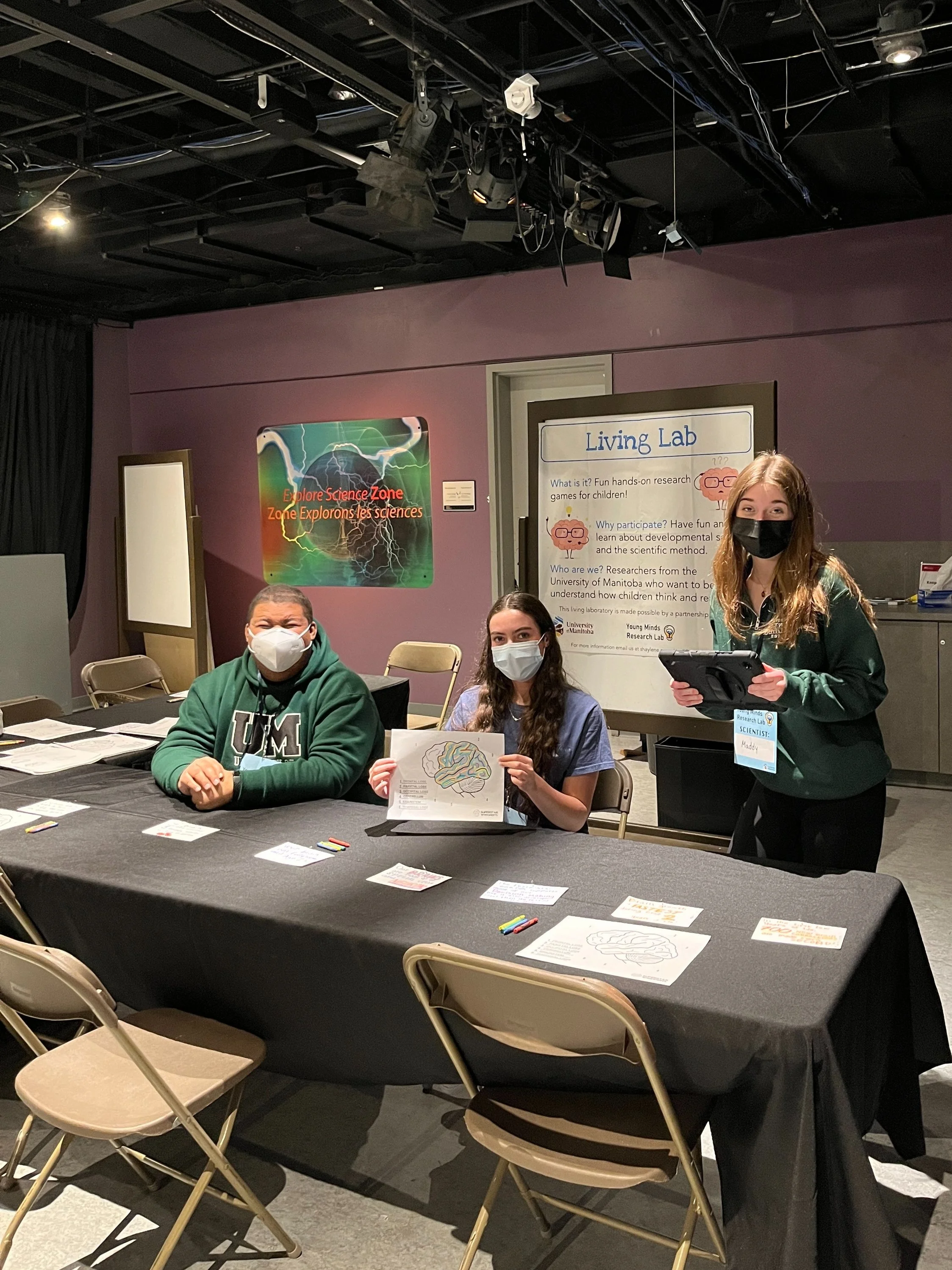

The Living Lab

We work in the community where we demonstrate the nuts and bolts behind research with children. Right now we are currently working with the Manitoba Museum to bring developmental science into the community.

Below we discuss some ongoing projects you might have seen at the museum. If you participated, thank you for supporting our research! This page outlines what we have been learning about child development in our studies so far. We hope to see you soon!

Check out our most recent newsletter for more information: https://www.youngmindsresearch.com/newsletters

Also check out these online safety tips from the Winnipeg police: https://winnipegpolice.substack.com/p/keep-your-kids-safe-online.

Data Ownership

Dates: Dec 2022 - May 2023

Overview

Children are using the internet more and more. When they use the internet, they often share personal data, like their name or their address. We already know that very young children understand that physical objects, like a bike, can be owned. However, we do not know as much about children’s understanding of digital items like their data. In this project, we are investigating how children think about sharing data online and if they view their data as property. In the study, children are told about a character who shares personal information like their school’s name, and general information they share, like kids, who go to school. We are then asking children who they think should be “in charge” of this personal information after it’s shared versus general information. We predict that older children will be more likely to think that they are in charge of the personal information that they share. If they reason in this way it would mean that they recognize that apps should allow them to make important decisions about their data. This project has important implications for children’s ability to recognize when apps might be violating their rights.

Results

We found that at around age 8, children begin to understand the difference between personal and general information. Older children (ages 8-12) think that they should be in charge of their own personal information instead of the game. Younger children (ages 4-8) did not recognize the difference between personal and general information. They were also unsure of who should be in charge of information. This study suggests that children can be educated earlier on who really has control of data once it is shared online. We are currently preparing this data for publication so check back in a year for the official paper!

Results Part 1:

Nancekivell, S.E. & Fahey, J. (2022). Who owns your information? Young children’s judgments of who owns the general and personal information users share with apps. In J. Culberston, A. Perfors, H. Rabagliati, & V. Ramenzoni (Eds.), Proceedings of the 44th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society.

Data Safety

Dates: Feb 2023 - March 2024

Overview

Children have large digital footprints. Their activity online, including information about their identities is turned into data that could be shared with other users and companies. Digital platforms should not be sharing information with others without their permission. In this study, we are interested in learning at what age children appreciate that apps sharing users’ personal information without permission is a violation of that users’ rights. Children see a story about a peer who plays a game that shares the peer’s personal information, such as their name and address, with other kids. We then ask children if they think the game is “nice” or “mean”. We predicted that although younger children may not understand who should be in charge of their data, they understand that their information should be protected.

Results

We found that by age 7/8, children evaluated a game sharing personal information more negatively (less nice and less desirable to play), than a game that does not. Younger children (age 5) did not view a game that shares personal information any differently than one that does not. Older children cared a great deal about permission or consent and viewed information sharing as acceptable when the user gave permission. We are currently preparing this data for publication so check back in a year for the official paper!

See this poster for a summary of the results.

Data Transfer Beliefs

Dates: Mar 2023 - Present

Overview

Some online apps require the transfer of personal information from the user to the app but little is known about how children represent this “transfer”. In this study, children are told a story about a character who shares personal information, such as their address, with an online game. We then ask children what they think the game is allowed to do with the information. We also ask what they think the character is allowed to do with the information. Children are shown different types of actions and asked to make judgments about them. We predict that children will think the character has greater rights over the information than the game. We also predict that children will deem actions that are lower risk (such as looking at information) as more permissible than actions that are higher risk (such as selling information).

Results

So far we are finding that children ages 8-11 years old will judge that apps should be able to do less with a user data’s than the user can. This includes sharing it with others and selling it. However, unexpectedly, children also think that people generally should not sell their data. In a recent follow-up where we compared information to a song we found that children likely view selling information as unacceptable because they are worried about the safety risks. Overall, children at this age seem to have complex beliefs about what it means to share information and how safe it is to do different things with personal information.

See this paper for a presentation of these findings at Cognitive Science!

Social Media Sharing

Dates: Oct 2023 - Present

Overview

Social media has become a part of everyday life for many people. Parents often share information about their children but we don’t know a lot about children’s perspectives on such sharing. In this study, children and parents are told a story about mothers who use social media to post videos of their children and of themselves. We manipulate whether the posts are positive or negative and who they are about. Across scenarios, we ask children and parents if the posts should remain up or be taken down and we are interested in how these factors (valance and content) affect their decision making. We think talking about these concerns is important in navigating social media usage and also helps support parent-child relationships when online.

In a follow-up study we are currently looking at how the motive for posting content on social media, to make money or for entertainment, influences children’s reasoning about the ethics of posting.

Results

So far we are finding that when young children make moral judgments about social media posts that they are more focused on how social media post appears than adults and older children. Adults and older children appear to think about other important factors like the child’s rights (whether they want the content posted) and the parents intent (whether they want to make money).

See this poster for a presentation of part 1 findings!

Museum Learning

Dates: Jan 2024 - Present

Overview

People are likely less interested in learning about a topic that they think they know a lot about. In this way, how much we think we know likely affects our motivation to learn. But, research suggests that people often do not know as much as they believe they do. This research project wants to understand how (and whether) we can increase visitors desire to learn about science in museums by revealing such thinking errors (i.e., over estimates of knowledge). Children (10-12 years old) and adult museum visitors will be asked about how they think about exhibits, and how interested they are in learning more about the exhibit after being asked. When describing how an exhibit works, we predict people will realize what they don't know (i.e., realize they have a thinking error) and will then want to learn more to fill in the gaps in their knowledge.

Results

So far, children and adults are showing an illusion of knowing where they think they know more about how exhibits work before being asked to explain their knowledge than afterwards. When we divided our sample by people who recognized they didn’t know as much as they thought and people who didn’t, we found some more interesting findings. Specifically, people who realized they were overestimating how much they knew sought out more information about the exhibits than people who didn’t. On average this group is requesting one more information sheet! We look forward to finishing this study this summer. Check back for our final findings later this year.

Photo Sharing

Dates: Jan 2024 - Present

Overview

Many apps allow children to take pictures. However, little is known about how young children think about apps taking pictures. In this study, children ages 5- to 8-years-old are shown a person and a cartoon version of the same person. We ask children if the app should be allowed to take pictures of the person or the cartoon character in different settings, like a kitchen or living room. We want to understand whether children think about privacy when sharing pictures with apps. We predict that children will think that it is a violation of privacy for the app to take pictures of the person, but not the cartoon. We also predict that children will think that certain settings, like a bedroom are more private than other settings, like a kitchen, and will judge that taking pictures in more private settings is less permissible.

In follow-up studies, we are currently examining how reminding children to keep information private and how the content of the cartoon photo influences children’s judgments.

Results

In the first part of this study, only older children (7- and 8-years-old) are appreciating how privacy rules affect when images should be shared. Children at this age 7- and 8-year-olds (but not younger) are judging it less acceptable for the game to take pictures of real Sally as compared to cartoon.

The first follow-up study is an ongoing study examining how a reminder might help children. This study isn’t done yet! But so far children are saying no pictures should be taken at all even for cartoon Sally. This suggests that telling children to keep things private might just make them cautious overall. We are exploring this finding further right now in the lab!